How Pietistic Thinking Poisons the Christian Mind

The Politics of Hovering 12 Inches Above the Ground

A new acquaintance of mine, Joel Webbon, recently published a book called “Fight by Flight: Why Leaving Godless Places is Loving Godless Places.” I haven’t read it yet, but from what I can gather, he makes the case that some places in America have become so hostile to the Christian faith that ordinary Christians should consider moving somewhere else.

For my part, I see this as perfectly reasonable. In scripture, many saints of God fled danger and sought safe haven from persecution (including Jesus’ own parents!). But Pastor Joel has received a lot of pushback on this from those who say that Americans are not persecuted like the early church, the NT calls us to suffer for Christ, and that Christians who flee “blue states” would deprive churches in those areas of the few faithful Christians that remain.

Interestingly, after this controversy begun, a good test case broke out of potential legislation in Michigan that would criminalize using the “wrong pronouns” for a transgendered person. And by criminalize, I mean it would be a felony, punishable by a fine up to $10,000 or even going to prison. This is no small matter. If this law passes the Michigan legislature, you could refer to a dude dressed up as a girl as “he” and be sent to prison for it.

If passed, this bill would threaten the free exercise of every Christian’s faith in the state, because Christians may not bear false witness. And should Christians flee this suffocating madness for the sake of their families, livelihoods, and consciences?

Some Christian leaders are arguing “no,” they should stay put and endure whatever suffering may come as a result. I think this thinking is wrong-headed because it is overly pietistic. In reference to one’s personal devotion to God, “piety” is a good thing. That’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about pietistic thinking, which views all of life through the lens of individual spirituality, without taking common sense, real-world implications into account.

The Politics of Hovering 12 Inches Above the Ground

People who think too pietistically tend to see their place in the world through the lens of their personal spirituality. I’ll admit, this is hard to pin down precisely, because I find myself in agreement with them on so many points. Yet at the same time, I’ve learned to recognize the pietistic impulse in other people because I’ve fallen prey to this type of thinking so many times myself.

I’m still working this out in my mind, but I’ve noticed a handful of things as a pattern with pietistic thinking. I used to hear an old adage, “he’s so heaven bound he’s no earthly good.” That’s a good shorthand for what I’m about to describe here.

Miracle Motif. Pietistic people are so heaven-minded that they struggle with real-world, practical, applications of their faith. This is especially true when an “ideal” they seek is out of reach. I’ve seen this with Christians who are fund-raising. I knew one guy who needed to raise a large amount of monthly support, so he decided to forego typical fundraising activities like phone calls, emails, and newsletters, and simply pray. Pray like crazy for God to provide. “It worked for George Mueller, God will provide!,” he thought. He expected God to circumvent the normal means of fundraising, and trusted God for a miracle instead. It didn’t work.

Boredom with the Ordinary. The flip side of the miracle motif, pietistic people tend to see the ordinary ways God’s providence operates in the world as less spiritual. They expect God’s providence to be out-of-the-ordinary, or even supernatural. For example, think of the conversion testimonies we get excited about. The conversion testimony of a drug-addict or prostitute elicits cries of joy for the amazing work of God. Children of Christian parents who profess faith are not quite as exciting. The testimony of a street thug is more exciting than the testimony of a child.

Combining the first two points, pietistic thinkers resist the idea of fleeing “blue states” because they believe God does miracles and expect him to perform them regularly. They think, “God is a big God and he’s going to show up BIG TIME and do this amazing work! Aslan is on the move!” Therefore, planting a church in NYC, LA, or Ephesus are all seen as evidence of God’s power, whereas the normal work of God in everyday life is not as notable. No one would say it out loud, but planting a thriving church in Manhattan “feels” like a bigger move of the Spirit than the same in conservative, bible belt, small town TX.

In my view, miracles are the exception, not the norm. God can and will do miraculous works as he pleases, but we should expect and prepare for God’s providence to usually work according to ordinary patterns of life, not miraculous. For example, I praise God for extraordinary conversion stories like Rosaria Butterfield and Beckett Cook who were saved from homosexual lifestyles in their adulthood. These stories powerfully remind us that God can save anyone from any sin. Yet the normative pattern for conversion is through the ordinary means of parents instructing their children in the faith (Deut 6). A kid becoming a Christian in an already Christianized culture almost feels like cheating. God didn’t have to do as big of a miracle to save that kid. It’s less exciting.

(For what it’s worth, the pioneering work of missionaries amongst unreached people groups is a separate issue from what I’m describing here.)

Binary thinking. Pietistic people tend to see things as being either sacred or secular. The sacred realm pertains to their personal spirituality: conversion, growth in Christ, bible reading, prayer, repentance, sanctification, church attendance, evangelism, church planting, and so on. These are the “things of God;” these are the things that really matter.

The secular realm is everything else: job, neighborhood, government and politics, finances, economics, culture, etc. Since these things have no direct, obvious bearing on one’s personal spirituality, they are seen as less relevant to the Christian life. If something does not have direct bearing on the salvation of souls, it is not something that Christians should devote much time and attention to. In other words, the world is not a place for Christians to pursue the dominion of Christ over every sphere, the world is merely a stage upon which we act out our personal spirituality. For example, I’ve heard people say things like, “you are devoting so much energy to arguing about politics while people are dying and going to hell!”

To be sure, every Christian regards spiritual, eternal things as of the highest importance. The difference is what constitutes “spiritual” things. Pietistic thinkers tend to limit the spiritual realm to those things most closely associated with his or her personal walk with God. As a result, pietistic people will tend to downplay God’s work through ordinary means. They tend to see God’s work through direct, divine causation, often as manifestly extraordinary and even miraculous, and tend to discount the notion of God’s work through ordinary, indirect, secondary causation.

Christianized cultures function as a sort of pre-evangelism. They supply the contours of belief by reinforcing norms, customs, and beliefs that are compatible with Christian belief. Therefore, it is good and right to develop and pursue strategies to ensure we live in cultures that are hospitable to the gospel. One could argue that having a Christianized culture has no direct, quantifiable, and observable impact on any particular evangelistic encounter. Further, since God does not require a pre-evangelistic culture to convert a sinner, it is unnecessary at best or foolish at worst to form cultural strategies. This view puts God to the test by neglecting the ordinary, cultural means He uses to convert sinners.

In my view, there is no divide between “sacred” and “secular.” Every square inch belongs to Christ and is under his Lordship. To be sure, one’s personal salvation and devotion to God is of greater concern than the culture we live in, but that does not mean we are free to neglect that culture. The culture we live in matters, not as a stage upon which we play out our spirituality, but as the realm within which we pursue the total dominion of Christ. We need to trust God not only for the conversion of souls, but also in the ordinary means of converting them.

Fetishize Suffering. For example, the Christian duty to faithfully endure suffering can be easily mistaken for a duty to pursue suffering. Conversely, any attempt to avoid suffering can be seen as a sinful lack of faith. So, if someone sees persecution on the horizon, a pietistic person would embrace it as the most faithful, Christian option, and see flight from persecution as a cowardice. Why? Because he’s mostly approaching the subject through the lens of his own spirituality. His binary thinking gives him only two options: obedience to God (stay and suffer) or disobedience to God (flee as a coward). Pietistic thinkers will resist the idea that God would genuinely and providentially work through a group of people to retreat to a place of safe haven while they regroup. This would be regarded as a sinful abandonment of one’s duty to God. Pietistic logic goes like this: if suffering for the Lord is a good thing, then we should seek to increase suffering to increase goodness.

Conclusion. Putting it all together, pietistic impulses cause Christians to approach life as though they are hovering 12 inches off the ground, keeping themselves pure and free from the stain of contact with the world.

Another acquaintance of mine, Nate Schlomann said this:

My problem is that I see people arguing against the *very idea* of having a strategy like this at all. They aren't arguing that this is a bad strategy. They are arguing that Christians shouldn't strategize in this manner. We can't even have the discussion.

We're a people who don't talk about big-picture, global ideas anymore. This is weird, given that we descend culturally from people who traveled oceans and vast continents to live strategically.

I think a lot of this has to do with end-of-history thinking. People think that the age of big movements and historical events is over. But I think we'll find out.

I get the appeal of this. Exercising dominion in the world is an ugly business. I have a friend who is a State Senator in KY. He helped push a bill through the state legislature that does the opposite of what Michigan is doing. He wants to ensure that Christians in KY have legal protection from the growing encroachments of the LGBTQ cult that would criminalize our faith. This means running for office, campaigning, fundraising, and having your name drug through the mud, all without any certainty of the outcome. And then, doing the work of legislating! My friend has faced angry mobs that think he’s the devil. It’s not “spiritual” work in the pietistic sense. He doesn’t enjoy the immediate spiritual payoff the way a personal quiet time can provide. But this is spiritual work, and I’m thankful for men like him doing it.

A Personal Story About How I Learned This Lesson

I wrote a story on Twitter this week about my personal experience with these themes:

When I first decided to plant a church in Cincinnati, I believed the godliest thing to do was move to the most dangerous part of the city. I felt as though it would be cowardly to go anywhere else. The harder the better. But I had doubts. So I sought counsel from a friend.

He basically advised me that there is no particular moral weight to where I choose to live and minister, and that I needed to proceed with a clear conscience. That was freeing. It helped me detect something in my own heart:

Doing the “Most Difficult Thing” became a sort of self-righteous litmus test in my heart, whereby I could judge others who were ministering in so-called “safer” areas. That was wrong. My friend’s counsel helped free me from a flesh-driven burden to appear more righteous.

In the end, being free of that moral obligation, I did end up moving to and planting a church in the inner city. I’ve been here 15 years. The lesson for me is this. God gives us freedom in Christ to live in more or less favorable areas to the Christian faith.

Flee blue states for safe haven in a red state? Fine. Remain in a blue state to influence your community? Fine. As a pastor in a red state in the heart of a blue city, I can respect those who move out and those who stay. God works through both.

More Sightings of God’s Good Design in the Wild

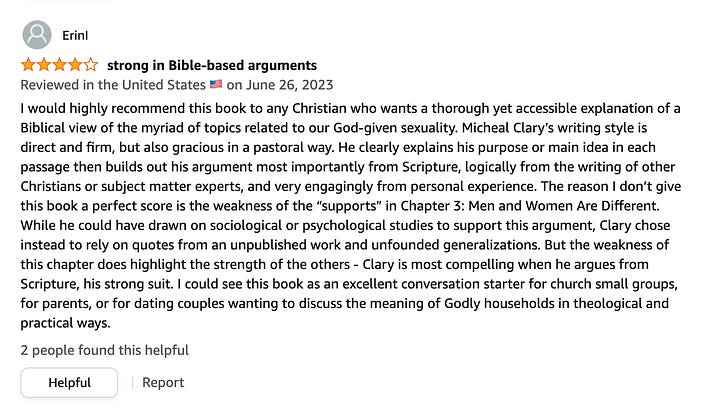

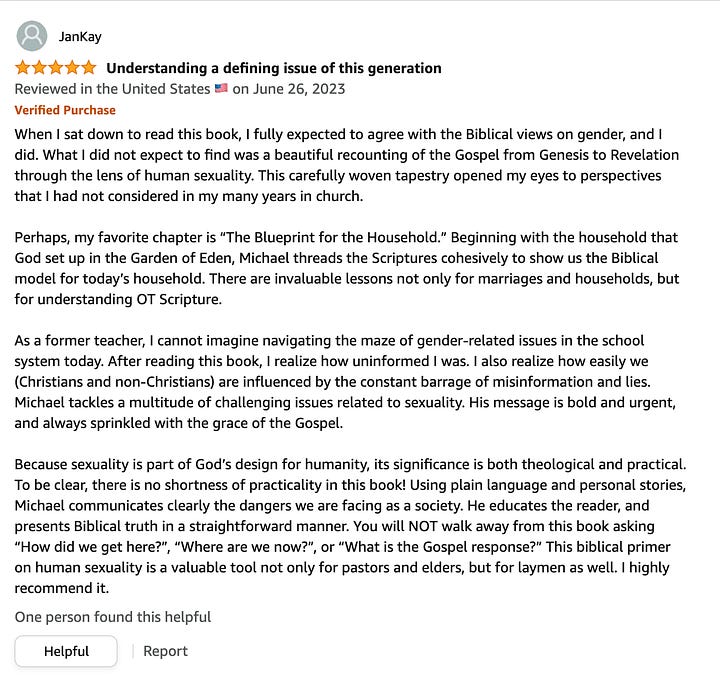

I recently had the opportunity to appear on the “Hard Men” podcast with Eric Conn. It was really enjoyable and I’m thankful for the opportunity. If you have any favorite podcasts that interview authors, please let me know and I can reach out and try to get on their show!

Here’s the show: The Hard Men Podcast with Eric Conn

Here’s the episode with me: Speaking Boldly on Sexuality with Pastor Michael Clary

GGD has even gone international! (Of course, it was a friend taking the book on an international flight… that count’s, right?)

The world has gone sideways. I'll control what I have the power to do so. Today at conclusion of our service, we were ask to grab an armband with a students name on it. Large church, many armbands. Our youth are traveling to Tennessee onTuesday for a week of fun and discipleship. With my eyes closed, I grab a band and will pray for this student all week long. I'll be praying for Alex C. this week. Prayers for safe travels. They come home on Saturday. This is something I have control over.