Emotional pain is the ultimate con job for a hypersensitive age. Christians care about hurting people, which is why we're so vulnerable to this kind of emotional manipulation. We need to break free from it and refuse to be fragile. In this essay, I break down, with biblical and practical counsel, how not to not be an emotional manipulator or be emotionally manipulated.

Have you ever noticed how subjective and suggestible emotional pain can be? Physical pain isn’t that way. No one needs to tell you that cutting your finger hurts. Your body lets you know.

Emotional pain is different. What people in one generation or culture finds very painful can be not painful at all in another time or place. In our culture, people give each other gifts on their birthday. If you expect a gift from someone and don’t receive it, you might get your feelings hurt. But other cultures don’t have that custom, so you wouldn’t be hurt by not getting a gift.

The feeling of pain is relative to one’s expectations. Unmet expectations can be painful, but not like physical pain, which is always painful. If something is emotionally painful in our time that wasn’t painful in some other period of time, that tells us that much of our emotional pain is subjective, suggestible, and ultimately, we have a degree of control over our experience of emotional pain.

Further, I would argue, in our day we’ve allowed ourselves to be tyrannized by our own sense of pain. Sometimes people can feel socially pressured to feel pain, simply because people around us act like we should be in pain.

A friend of mine went through a breakup with a girlfriend recently. Immediately, everyone started consoling him and treating him as though he’d just experienced something traumatic. However, he took it all in stride. It was no big deal to him. He simply said, “it didn’t work out, and I’m cool with that.” But if he’d reacted according to these social cues, he could have acted devastated. If he’d acted like he were crushed and utterly heartbroken, he could have been rewarded with lots of sympathy and attention.

That’s probably the culprit in many cases. Being in pain gets us sympathy and attention, and most people like that. You feel loved when people come to your aid and show you compassion. Thus, expressing emotional pain can be a socially rewarding experience, which incentivizes further expressions of pain. Before you know it, you’re a hot mess all the time which is fueled by ever escalating expressions of pain.

One of my main concerns in this matter is emotional manipulation. Christians are naturally drawn to people who are hurting. These days, people know that expressing pain is a sure way to garner sympathy from Christians, and even to control them. All someone has to do is say, “I’m hurt,” and they become the marionette pulling the compassionate Christian’s strings.

This happens at the interpersonal level, but it also happens more broadly, as churches and even whole denominations can be emotionally manipulated by people who have learned that they can hold power over them simply by turning their Christian compassion against them. (See Joe Rigney’s book Leadership and Emotional Sabotage for more on this).

Pain is Suggestible

We may not like admitting this, but much of our emotional pain is felt through the power of suggestion. We wouldn’t have necessarily perceived an incident as painful until someone else suggested it to us. In other words, we can be socially conditioned to feel pain for things that wouldn’t have otherwise been considered painful, or at least not as painful.

How does this happen? Some things we feel are painful occur because a social norm was violated, and someone suggests to us that we should feel pain as a result. Going back to my birthday gift example, there’s no law or moral obligation for anyone to buy anyone else a birthday gift. If someone doesn’t buy me a birthday gift, I shouldn’t get upset about it.

But suppose the next day, I tell someone, “I didn’t receive any gifts on my birthday.” And suppose they immediately recoil in horror, with expressions of shock and sympathy, and say, “oh! I’m so sorry! That must have been so hard for you! How are you doing today? Are you OK?”

My friend’s reaction suggests that emotional pain is the most natural response, and also that I would be showered with sympathetic attention if I act hurt by it. Suppose I go a step further, and start telling other people how “hurtful” it was that they did not buy me gifts. I’ve now crossed into emotional manipulation territory, because I’m trying to elicit compassion from people while guilt-tripping them for violating an improper standard.

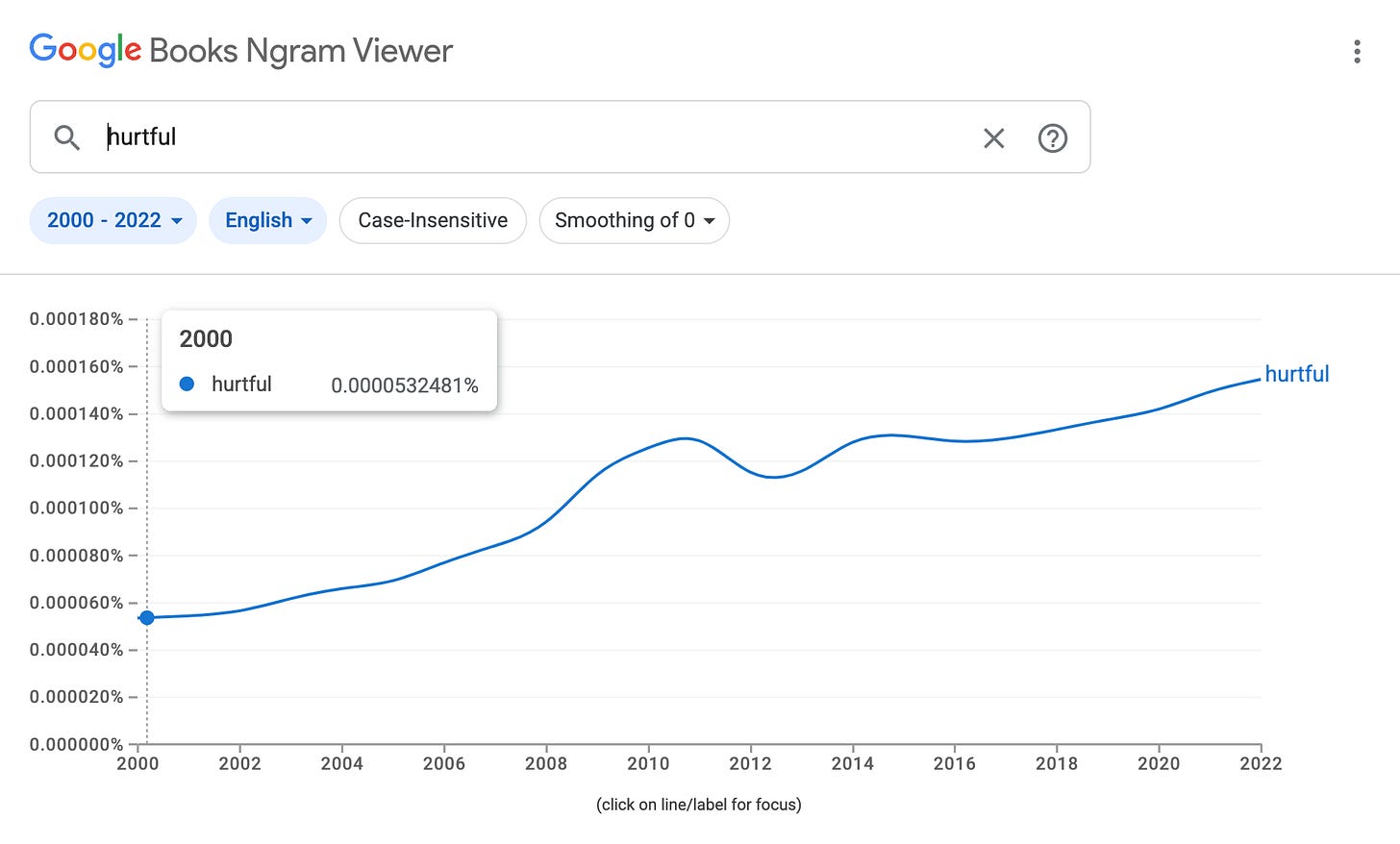

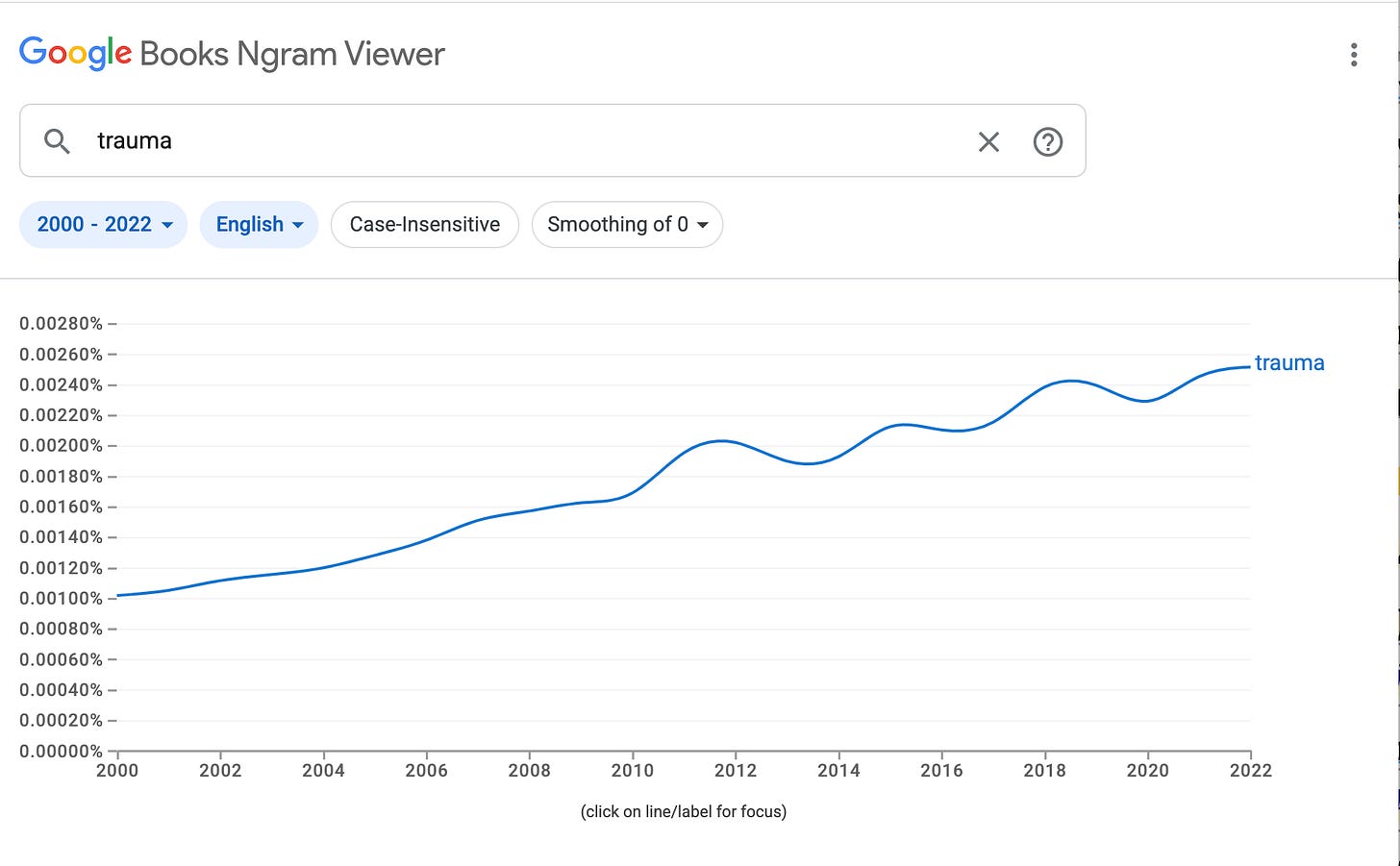

Google Ngram searches indicate the pain oriented words like “hurtful” and “trauma” have been on the rise in the last two decades.

Pain is Communal

There’s another layer to this phenomena: pain is also communal. Pain-sharing can be a bonding mechanism people use to feel closer to each other. When lots of people feel pain for the same reason, the bonding effect multiplies. That’s why support groups of various kinds are so popular. This phenomena was vividly depicted in the film “Fight Club,” where Edward Norton’s character spent his evenings infiltrating various support groups for trauma-bonding.

People bond over pain by saying things like, “tell me how badly you were hurt by this. I want to listen to your pain and hold your story. Then, I’ll tell you my pain, my story, and how hurtful it was to me, too.” Don’t underestimate the power of pain to bring lonely people together.

How Pain Becomes a Tool of Manipulation

There’s a concept creep with pain and the words we use to describe it. Take the word “hurtful,” for example. People who have done nothing wrong may nevertheless find themselves accused of doing something “hurtful.” The only evidence provided is the feelings of the accuser. To them, pain is sovereign.

This kind of emotional blackmail happens all the time, and it can only happen in a society where truth takes a backseat to emotions. And pain is the most sovereign of all emotions.

Children do this all the time. They do something that didn’t actually hurt, but they look over at their mother to see her reaction. If she looks concerned, turn on the waterworks.

Adults do it too. When people are opposed to something but lack a good argument against it, they talk about the “pain” that course of action would cause. It’s quite an effective strategy. It works because it bypasses the cognitive faculties and appeals directly to the heart.

Sometimes, if one person’s pain isn’t quite enough, they may call an anonymous “cloud of witnesses” to testify on their behalf. They say things like, “I’m not the only one who feels this way” and “I’ve heard from several others who are also upset.”

This tactic is particularly gross because it makes the speaker sound like merely a brave representative for an invisible, disgruntled army ready to beat down your door. People who do this may not consciously realize they are being manipulative, but that’s what it is.

“Church Hurt”

Churches are especially susceptible to this kind of emotional manipulation for two reasons. First, pastors care for their flocks, feeling compelled to care for the hurting and bind up wounds of the brokenhearted. Second, church members know this, and they, too, view the pastoral primarily through the lens of caring for those who are hurting. They believe the pastor’s primary duty is to heal everyone’s pain, no matter the cost. If people feel hurt because they didn’t get their way, they turn it into an accusation against the pastor, whose actions are considered “hurtful.”

Thus, a faithful pastor who truly cares hurting people may be vulnerable to emotional manipulation, because his compassion can be weaponized against him, often to the detriment of the church.

Here’s some examples.

Someone is “hurt” because the pastor didn’t condemn an act of racism that was in the news that week

The pastor preaches against abortion and people worry about the “hurt” it will cause to women who have had abortions

Someone is worried that their unbelieving LGBTQ friend that’s been visiting recently will be “hurt” by the pastor’s preaching against homosexuality

A single man or woman feels “hurt” because the church talks about marriage and family too much, making them feel unwanted

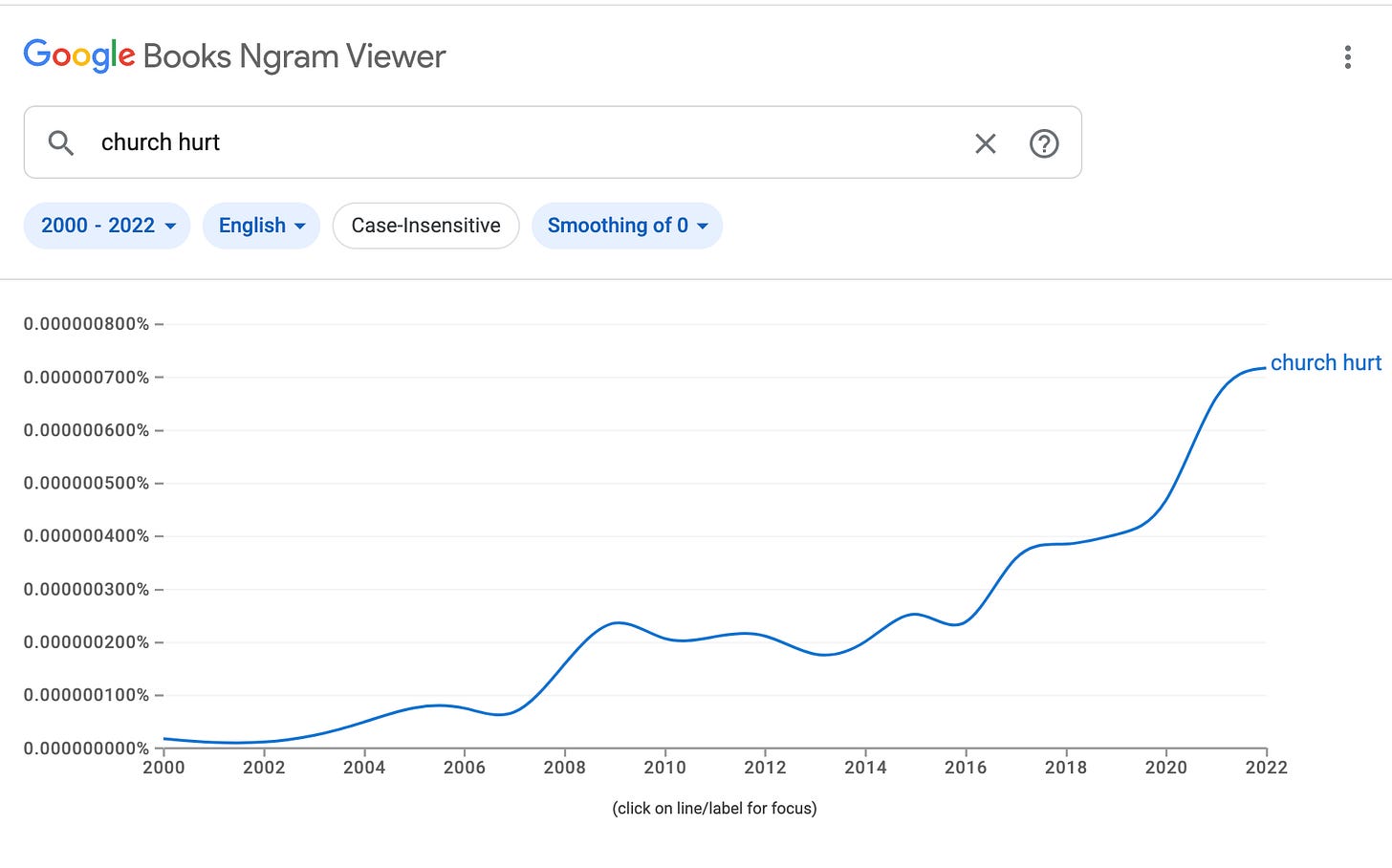

Again, we can see “church hurt” becoming quite popular in the last twenty years, especially since 2020.

Pain is Not Sovereign

Christians, pain is not sovereign. In fact, pain is necessary for true Christian growth. Sanctification often hurts, but it’s the kind of hurt that God uses to transform us.

God’s word is described as a sword, and swords were made to cut. It hurts when we get cut, but biblically speaking, that kind of pain is good. Scripture is profitable for things like teaching, reproving, and correcting, which means confronting our own ignorance and errors with truths we’d rather avoid. That may hurt, but it’s the kind of hurt needed to grow.

Conclusion: How to Resist this Temptation

So, what do we do about this? I have two suggestions.

First, don’t automatically assume the legitimacy of emotional pain. When you feel hurt by something someone said or did, don’t simply assume the other person is in the wrong. Diagnose whether or not the pain is actually related to a real offense, or if it’s just unpleasantness or discomfort that you’ve promoted to the level of pain. The pain might be an invention of your own mind, or it may be pain you feel through the power of suggestion or social pressure.

To diagnose it, ask yourself these kinds of questions:

Is what they said true?

Did they violate a clear biblical standard in what they said/did?

Is the pain I feel a conditioned response based on how others have reacted in similar situations?

Am I upset by something because all the people around me are also upset and I gain a sense of belonging by sharing their grievances?

You may find that the other person wasn’t actually in the wrong, you just didn’t like what they said. If that’s the case, then the problem is you. If you accuse someone else of wrong based purely on your emotions, then you are actually in the wrong and inflicting a real pain.

False accusation is a sin. Consider these texts:

“You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor” (Ex 20:16).

“If a malicious witness arises to accuse a person of wrongdoing, then both parties to the dispute shall appear before the Lord, before the priests and the judges who are in office in those days. The judges shall inquire diligently, and if the witness is a false witness and has accused his brother falsely, then you shall do to him as he had meant to do to his brother. So you shall purge the evil from your midst.” (Deut 19:16-19)

“Unequal weights and unequal measures are both alike an abomination to the Lord” (Prov 20:10).

If you continue to nurse this grievance because you feel hurt, you are giving in to a sinful passion that you should mortify instead. If you feel hurt because everyone around you feels hurt, then you are allowing yourself to be emotionally manipulated by them. Take responsibility for your own feelings. Do not let the feelings of others control you.

Second, change the way you talk. Consider issuing a moratorium on words like “hurtful” or “trauma” or “wounded” unless you can identify a specific sin committed against you.

Words have power. You may be surprised by how a simple refusal to talk about your pain can help free you from it. You may even end up feeling hurt less often (which is another way of saying, you’ll get emotionally stronger). You can starve your pain by refusing to stew on it and constantly giving it attention.

Don’t let your pain define you. Refuse to be fragile. Trust God, and rise above it.

Future Proof Christianity Conference, May 8-10 in Cincinnati

If you want to learn about becoming a high-agency Christian from experienced pastors who know what it takes, the “Future Proof Christianity” conference in Cincinnati/Northern KY is for you.

In the years to come, Christians need to be rugged. Believers with a backbone, unshaken, unapologetic, and prepared to thrive for generations.

At Future Proof Christianity, we’re calling believers to anchor themselves in the unchanging truths of Scripture and apply them to every area of life.

Speakers: We’ve got a stellar lineup of speakers for the Future Proof Christianity conference sponsored by King’s Domain. You’ll hear keynote addresses from Jeff Durbin, Joe Rigney, C.R. Wiley, Tom Ascol, Michael Foster, David Schrock, and Michael Clary.

Website: www.futureproofchristianity.com

Dates: May 8-10, 2025

Location: Christ the King Church (638 Highland Avenue, Ft. Thomas, KY 41075)

Cost: $120 (early bird pricing is $110 through the end of February).

I’d love to personally invite all readers of this newsletter to come and join us this year!

(For sponsorship options, send us an email and we’ll get you more info!)

Family members of dysfunctional families are experts in emotional manipulation. That is why it is important for such members to find strong examples of family members to look up to. The church should have emotionally strong and sound family members that others can look up to. In other words, be an example.

This is a great article. Thank you!

Hey Michael, I appreciate many of the concerns you raise in this article. You are right that emotional manipulation is real. It happens in personal relationships, in churches, and even at a cultural level. Pain can be used as a tool of control, and Christians—rightfully drawn to compassion—can be exploited by those who leverage their suffering to gain sympathy or power.

I also agree that pain should not be sovereign. The Christian life is not about being ruled by our emotions but about submitting all things—including our suffering—to the lordship of Christ. As you point out, sanctification is often painful, and growth sometimes requires us to endure discomfort rather than avoid it.

But here’s where I believe your argument becomes dangerously simplistic, could prove significantly harmful if not balanced out, and why I'm choosing to put some work into a response: In trying to guard against emotional manipulation, you risk swinging to an extreme that denies the real, God-given purpose of pain—which is to alert us to what is broken so it can be healed.

While it’s true that some emotional pain is socially conditioned and that we must guard against using it manipulatively, not all pain is an illusion. Not all pain is weakness. Not all pain should be ignored or dismissed simply because it might be subjective.

A broken heart, a betrayal, a childhood wound, spiritual abuse—these things don’t cease to be real just because they cannot be measured like physical pain. To suggest that people should “starve their pain” by refusing to acknowledge it is not a call to strength—it is a call to emotional suppression. And suppression does not make wounds disappear. It drives them underground, where they fester and shape our lives in ways we don’t even recognize.

Unacknowledged wounds do not heal. They become the very thing you warn against: tools of manipulation. The man who has not dealt with his wounds will inevitably inflict them on others—often unconsciously.

One of my biggest concerns with your argument is that it seems to indicate that naming pain equals being controlled by it. But throughout Scripture, we see godly men and women naming their pain before God—not as a way of manipulating others, but as a way of being honest.

David poured out his sorrow in the Psalms. He didn’t “starve” his pain—he brought it before God and found healing there (Psalm 13, Psalm 34:18).

Jesus did not dismiss suffering. He wept with Mary and Martha at the tomb of Lazarus (John 11:35), even though He knew He would raise him.

Paul openly acknowledged his afflictions. He spoke about his hardships, his weaknesses, his "thorn in the flesh"—not to manipulate, but to show the power of Christ in his suffering (2 Corinthians 12:9-10).

You rightly acknowledge that pain is necessary for sanctification, but contradict yourself by suggesting that we should suppress pain. If pain is a tool God uses for growth, why should we ignore it? Rather than suppressing pain, the biblical model is to bring it into the light where it can be redeemed (2 Corinthians 1:3-4). There is a profound difference between dwelling in pain for attention and bringing pain into the light for healing. Your article does not allow for this distinction, and that is where it becomes spiritually and pastorally dangerous.

Your recommendation to issue a moratorium on words like “hurtful,” “trauma,” or “wounded” unless a clear sin can be identified is particularly concerning. Yes, words have power. And that is precisely why removing the language of suffering does not make suffering disappear—it only makes it unspoken.

Telling someone they cannot name their pain unless they can prove a clear sin has been committed against them is not a call to resilience. It is a form of emotional legalism that forces people to suppress their wounds until they become undeniable. This approach does not create stronger Christians. It creates disconnected, numb, and repressed Christians. And numb people are far easier to manipulate than those who are emotionally whole.

Refusing to name pain does not eliminate it. It simply ensures that it remains hidden, where it will continue to exert its power in unseen ways. Unprocessed pain does not stay buried—it surfaces in anger, in emotional detachment, in addiction, in relational dysfunction, in generational trauma.

This is precisely how implicit memory works. Painful experiences are stored deep within us, even when we do not consciously remember them (Siegel, The Developing Mind, 2012). Many people, particularly those who have been conditioned to suppress their pain, cannot even access their true emotions until they "borrow" them from someone else. A mentor, a counselor, or even a friend expressing anger or sorrow on their behalf can be the first step toward them feeling what they have been taught to ignore.

For example:

A counselor might say, “That wasn’t okay. That should have never happened to you.” And suddenly, the person begins to feel anger—anger they were never allowed to feel before.

A friend might weep over someone’s suffering when they are still too numb to cry themselves.

A mentor might say, “I would have fought for you. I would have protected you.” And suddenly, the deep grief of never having had that protection rises to the surface.

This is not manipulation. This is emotional permission. It allows people to reconnect with their own hearts in a way they could not do alone. You emphasize personal responsibility over emotions but downplay the biblical role of community in healing. Scripture teaches that we are to ‘bear one another’s burdens’ (Galatians 6:2) and to ‘mourn with those who mourn’ (Romans 12:15). Healing is often communal—not just an individual effort. The solution to emotional manipulation is not isolation, but healthy, God-centered relationships that allow pain to be processed truthfully. I've heard it said, "What is broken in relationship is healed in relationship."

Ironically, your article—written to warn against emotional manipulation—contains its own form of emotional control. By suggesting that people should suppress their pain and avoid words that name suffering, you are encouraging a culture of emotional suppression. By implying that acknowledging pain makes someone weak or manipulative, you are pressuring people to deny their own experiences. By framing avoidance as moral superiority, you are setting up a false dichotomy between resilience and emotional honesty.

In doing so, you risk creating the very problem you want to avoid. The less people are allowed to name their pain, the more likely they are to use passive-aggressive or manipulative methods to express it. When suffering has no legitimate voice, it will find an illegitimate one.

We can definitely agree on this: pain should not rule us. It should not be used to control others. It should not be sovereign.

But pain does have a purpose. It is a warning system that something is wrong. It is an invitation to healing. And most importantly, it is the very place where Christ meets us. Jesus did not overcome suffering by avoiding it. He went through it. And He calls us to do the same.

To deny pain is to deny the very process through which God redeems us.

Michael, I like you. I believe your core concern is valid. You want to protect people from manipulation and help them grow stronger in Christ. That is a noble goal.

But your solution lacks the necessary nuance. In trying to prevent people from being ruled by their emotions, you risk teaching them to suppress the very emotions that need to be healed. And in doing so, you may actually cause more harm than the problem you are trying to solve. This article may actually be leading people away from the gospel, rather than towards it.

The answer to emotional manipulation is not emotional suppression.

The answer is emotional honesty under the authority of Christ.

That is the path to true strength and avoiding "loser theology."